Tanzania’s history

After the end of the German colonial period during the First World War, the territory was divided among the victorious powers of Great Britain, Belgium and Portugal. The “Tanganyika Territory” went to Great Britain under a League of Nations mandate. After the Second World War, Tanganyika became a UN mandated territory under British rule.

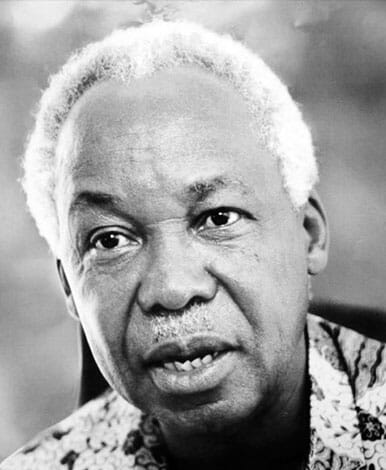

Julius Nyerere

In 1954, Julius Nyerere, a teacher, organized a political party, the Tanganyika African National Union (TANU). In May 1961 Tanganyika gained autonomy and Nyerere became prime minister under a new constitution. Full independence was granted on 9. December 1961. Nyerere was elected president when Tanganyika became a republic in the Commonwealth. In 1964, the states of Tanganyika and Zanzibar merge to form the United Republic of Tanzania. For the first 25 years of its independence, the country was ruled by Nyerere. He dreamed of a socialist society, introduced Swahili as the unifying national language, promoted the ideals of the Ujamaa (family) and political initiatives at the regional level.

Thanks to his vision, Tanzania is today one of the most stable states in Africa without major religious and ethnic conflicts. The severe economic crisis beginning in the late 1970s made reform inevitable. The state-controlled economy was gradually transformed into a liberal market economy, and market access was made easier for foreign investors. The one-party government ended in 1995 with the first parliamentary elections. Since 2015, John Magufuli has been in office as the fifth president.

Tanzania’s Economy

Despite its economic growth rates, Tanzania is one of the poorest countries in the world. GDP per capita was $3240 in 2017. Tanzania ranks in the bottom sixth of UNDP’s Human Development Index (as of 2019: 159th out of 189 countries covered). For numerous Tanzanians, life is a daily struggle. The official unemployment rate is reported to be around 13 percent, but is likely to be significantly higher. The average monthly income was USD 76 in 2017, while the share of official development assistance is USD 40 per capita.

With a gross domestic product share of 46 percent, Tanzania’s economy depends largely on the performance of the agricultural sector. The Agricultural sector employs more than 75% of the workforce. In Tanzania, subsistence farming is the main activity. The most important export goods from Tanzania include products such as coffee, cotton, sisal, tobacco and tea, but above all rubber and cloves. The development of agricultural export production is basically on the right track, but exports of raw products still predominate. Refining, which would bring a much higher profit margin, is still left to other countries due to a lack of capital, capacity and skilled workers. Consequently, there is an urgent need to diversify the range of exports and sources of foreign exchange. Industry in Tanzania is marginal and limited to food processing and petroleum refineries.

For several years Tanzania has been convincing with constantly high economic growth rates. In 2019, real GDP growth in Tanzania was estimated to be around 7 percent year-on-year. However, these figures hide the fact that 90% of the population does not participate in the overall economic growth. Poverty is and remains the central issue, especially in rural areas – two thirds of Tanzanians live on less than USD 1. 25 per day. Hand in hand with poverty are inadequate schooling and education, a lack of knowledge about the country’s two major health scourges, malaria and AIDS, as well as ever-increasing population pressure coupled with steadily declining arable land and yields.

In recent years, the country has also been hit by waves of inflation affecting all areas of daily life. Prices are skyrocketing, whether for staples like rice, corn or flour, for gasoline/diesel, electricity, cement or wood. It is precisely the increase in the price of everyday goods that has a dramatic effect on people’s living conditions.

The strengthened private sector in cities must not hide the fact that little has been done at the institutional and political level. Anyone who has a business in the service industry complains about the poorly trained employees and their unwillingness to perform. Others are concerned about their heavy dependence on imports. Since nothing is produced domestically, virtually everything, from computers to vehicles, fuel to clothing, furniture, dishes to books, must be imported. Customs duties, import taxes and other import barriers make small and medium-sized enterprises in particular vulnerable to arbitrary action by the authorities. The World Bank ranks Tanzania 141th out of 189 countries (as of 2019) in terms of the climate favourable to opening a business. Criticisms include: excessive bureaucracy and corruption, difficulties in acquiring land and real estate or obtaining building permits, problems in electricity supply, import and export, and high tariffs.

All these reasons make investment attractive only to those investors who do not care about money and who have the right key relationships. These include mining, large Arab or Indian hotel and construction projects, and the telecommunications industry. All the sectors mentioned face the same challenges: investment is extremely capital intensive, while creating comparatively few jobs. Only a few benefit, including corrupt politicians, domestic big industrialists and foreign financiers.

The same goes for development aid and foreign financial aid. A large part of international development cooperation in Tanzania, (more than one third) is concentrated on the health sector. Other areas include the development of infrastructure and educational facilities. In addition to Germany, Tanzania’s most important bilateral partners are the USA, Great Britain, Japan and the Scandinavian countries, especially Sweden and Denmark. Furthermore, China has become a close partner for Tanzania. The People’s Republic has invested heavily in infrastructure, health, education and military support, and is therefore valued as a business partner by the Tanzanian Government. However, China’s role in Tanzania’s development is controversial: accusations of corruption and exploitation of Tanzania’s natural resources are recurring criticisms of China’s Tanzania policy.

Corruption is one of the biggest obstacles to the country’s development. On Transparency International’s Corruption Index, it ranks 96th on the Corruption Index. of 198 seats (as of 2019). Whether in business, politics or even in the private sphere, it terrorizes and paralyses the country. Politicians divert money from development projects, perhaps not surprising. But businessmen also have to bribe in order to be able to import goods, to obtain residence permits and business licenses or to register a vehicle. In daily traffic, corrupt police harass locals and foreigners. Money can be used to bend the law, to fake the son’s university degree or to buy adequate hospital treatment.

Infrastructure is similarly problematic. Electricity and water supplies are insufficient. Some improvement can be seen in road construction, where many long-announced or halted road construction projects have been pushed forward in recent years. A modern railway line is currently being built between Dar es Salaam and Dodoma. Nevertheless, the transport system is nowhere near as efficient as it should be for a country with such growth rates.

Despite all the euphoria about the upswing, sustainability remains an open question. Economic performance is geared towards maximising profits, which does not leave out the large investor or the medium-sized young entrepreneur. Investments must be amortised immediately; Tanzanians have at most a mild smile for amortisation periods of 20 – 25 years or longer for construction projects as in the West. Local entrepreneurs pay their employees even lower salaries than expats and rarely invest in employee training. Low business knowledge is compensated by high sales prices; there is little awareness of quality, customer friendliness or even environmental considerations.

What is difficult to quantify is the informal sector, which dominates economic life in both rural and urban areas and has deep cultural roots. Thus, almost the entire basic supply of the population is based on informal economic activity, whether by fishermen from next door or the tomato seller from down the street.